by Luana Centorame

Share

What is artificial intelligence?

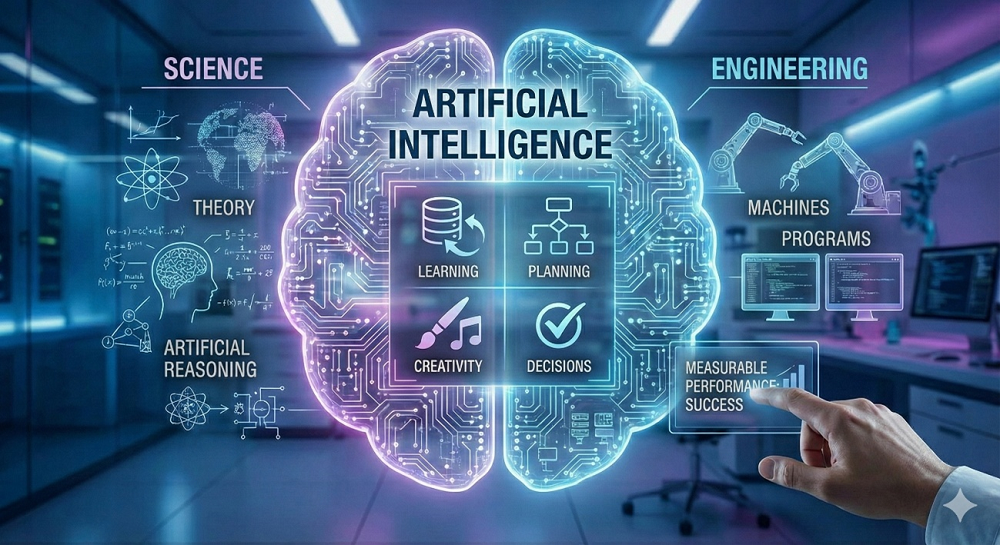

Artificial intelligence (AI) is the ability of a machine to exhibit human capabilities such as reasoning, learning, planning and creativity (European Commission definition, 2018). AI is both science and engineering. It is science because it theoretically studies how “artificial reasoning” might work. It is engineering because it builds machines or programs that actually realize these abilities.

The main goal of AI is to develop algorithms, models and systems that enable machines to learn from data, draw conclusions, make decisions, and solve problems autonomously as if it were a human. An AI system works when its performance is measurable and verifiable. For example, whether the machine solves a problem, performs a task, or makes decisions successfully according to predetermined criteria.

Fig.1: AI: science and engineering.

Machine Learning and Deep Learning

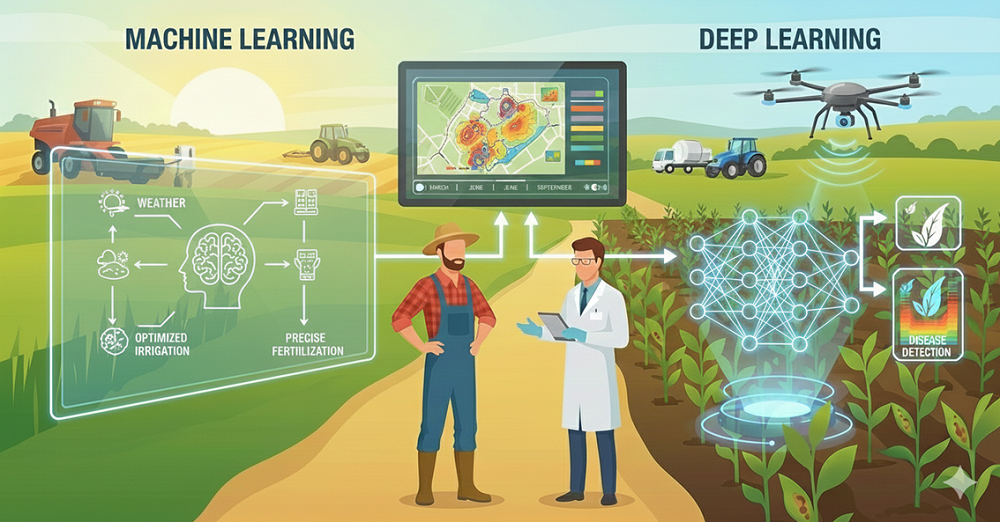

Machine learning and deep learning are two artificial intelligence technologies that are also increasingly entering the daily work of farmers and field technicians as practical tools for making better decisions.

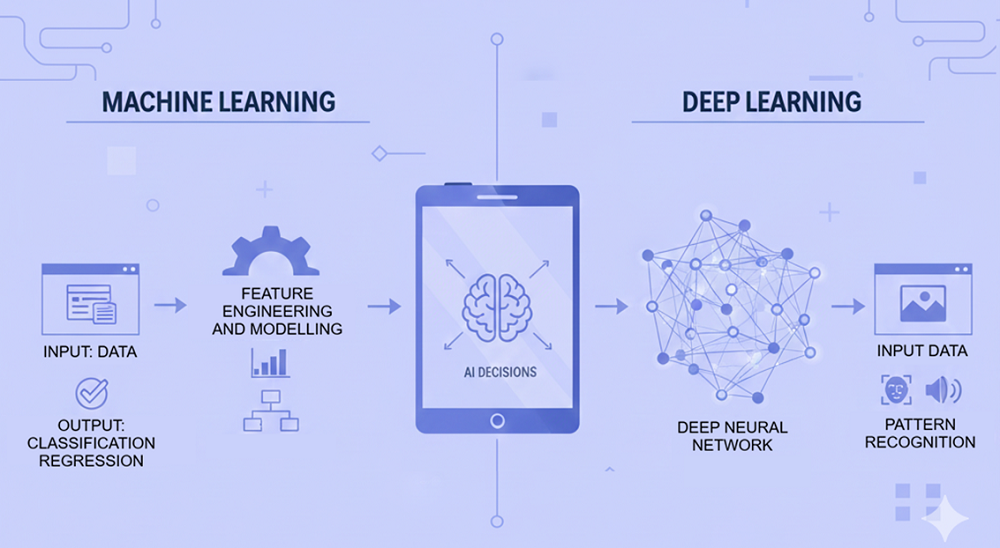

Machine learning can be described as the ability of a system to “learn from experience.” In practice, a lot of historical data is provided to the model: weather data, production data, soil analysis, crop images, agronomic interventions and their results. By analyzing this data, the algorithm automatically identifies recurring relationships, called patterns, and uses them to make predictions or suggest actions. In agriculture, this means, for example, estimating expected yield, predicting a risk of water stress, or identifying conditions favorable to the development of a disease based on actual environmental and agronomic data.

Deep learning is a subset of machine learning that is particularly powerful when working with complex data such as images, signals, or highly detailed time series. Its strength is the use of “deep” neural networks, inspired by the workings of the human brain, which can automatically extract the most relevant information from the raw data. In the agricultural context, deep learning is what makes it possible, for example, to recognize a foliar disease from a photo taken in the field, distinguish pests from the crop, analyze the structure of a plant’s canopy, or assess the state of vigor from satellite or drone images.

Fig.2: Machine Learning and Deep Learning.

The practical difference between the two approaches is that machine learning works very well when the key variables are already known and measurable, such as phenological data, yield, weather conditions. Conversely, deep learning becomes essential when the information is not immediately numerical but must be interpreted, as in the case of aerial imagery. Often, in more advanced agricultural applications, the two technologies are combined: deep learning extracts information from images or sensors, and machine learning integrates it with weather, soil, and agronomic management data to support the final decision.

Is AI really useful in agriculture?

The value of artificial intelligence emerges most when it is applied to real problems and properly integrated into business decision-making processes. The utility of machine learning and deep learning techniques lies in supporting the farmer in an increasingly complex and random environment of climate variability, rising production costs, increased regulatory pressure and the need to reduce environmental impact.

Currently, through the use of farm weather stations, satellite and drone imagery, in-field or tractor-mounted sensors, agriculture has a wealth of data at its disposal. The data must be turned into information for the farmer himself, to support him in making informed and sound decisions. One of the cruxes of modern agriculture is the need for

Managing spatio-temporal variability

One of the greatest advantages of using AI is the ability to work on spatial and temporal variability in agricultural systems. Seemingly homogeneous fields may have significant differences in soil, vigor or phenological development. With machine learning and deep learning, these differences can be detected and quantified, allowing for targeted interventions and, as a result, more efficient use of water, fertilizer and pesticides. This is a win-win approach, on the one hand reducing costs for the farmer and on the other increasing social, economic and environmental sustainability.

However, it is crucial to clarify that the effectiveness of these tools is highly dependent on the quality of the data and the correctness of the underlying agronomic model. An algorithm cannot compensate for missing, unrepresentative data or incorrect agronomic interpretation of the problem. This is why a multidisciplinary approach is crucial: cooperation between farmers, agronomists, technicians and artificial intelligence experts is needed to ensure the best performance of AI applied to agriculture. Machine learning and deep learning algorithms work best when they are built on a solid agronomic foundation and are used as supporting tools, capable of transforming large amounts of data into more timely, targeted and sustainable operational guidance.

Fig.3: The use of Machine Learning and Deep Learning in agriculture requires a multidisciplinary approach.

AI in citrus groves: a real-world case study

A concrete example of the application of artificial intelligence and digital technologies in agriculture is themultispectral drone analysis conducted on a citrus grove located in Sicily. The aim of the activity was to objectively and quantitatively assess the vegetative state and response of plants to different agronomic products (biostimulants), exploiting very high resolution images and advanced analysis algorithms.

The study area was divided into 25 experimental plots of 80 m² and including 4 plants each. This approach allowed us to obtain comparable and statistically robust data, which were essential for evaluating the efficacy of the treatments tested and for correctly interpreting the spatial variability of the citrus grove.

The survey was performed very quickly using a DJI Mavic 3 Multispectral drone, whose built-in multispectral sensor allows simultaneous and aligned acquisition of four spectral bands (green, red, Red Edge and NIR), in addition to the high-resolution RGB image.

Fig.4: Experimental plots within a Sicilian citrus grove.

The results of the experiment

From the RGB and multispectral images, a 3D model (digital twin) of the citrus grove was recreated. The use of this model coupled with computer vision and AI algorithms allows the automatic extraction of several biometric and physiological parameters of the crop, potentially on a plant-by-plant basis: vegetated area, to quantify canopy cover; canopy thickness, height, and volume, direct indicators of vegetative development; and vegetation indices, particularly NDVI for vegetative vigor, GNDVI and NDRE for indirect estimation of chlorophyll concentration and nutritional status. These parameters are derived from the application of advanced analysis algorithms that transform the raw data into agronomic information. Multispectral images, complex by definition, are processed to extract spatial patterns and differences between plots that would be difficult to detect with traditional visual observations.

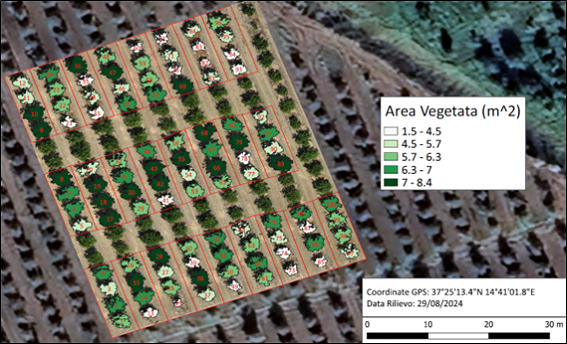

Let us look at two examples of biometric parameters calculated on the citrus grove. First, the vegetated area represents the canopy density of each individual citrus plant and is critical for visualizing the spatial distribution of density, identifying areas of lower or higher density.

Fig.5: Canopy area for each plant.

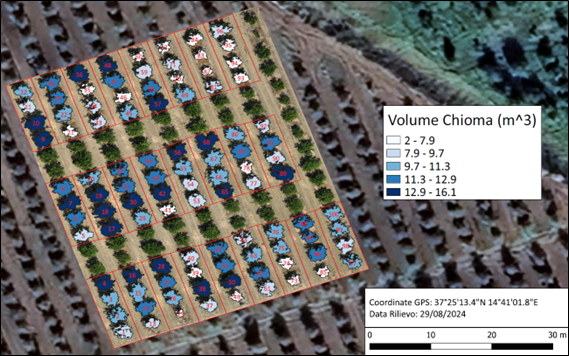

The canopy volume map allows visualization of overall canopy development as an average value for each plot. Canopy volume is directly related to biomass and traces the findings of the previous vegetated area map.

Fig.6: Canopy volume for each plant.

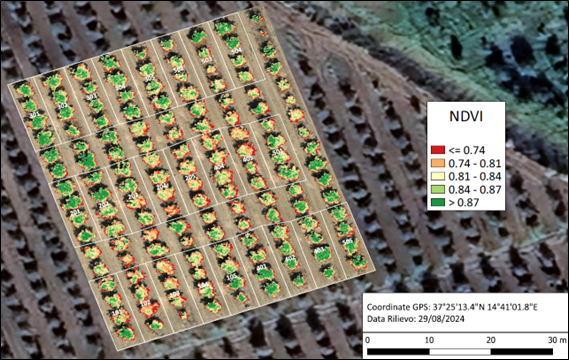

Based on the multispectral information captured by drone, three vegetation indices were calculated: NDVI, GNDVI and NDRE. The NDVI index is strongly influenced by the vigor of the vegetated area but is similarly limited by it because, after reaching a maximum point, it tends to saturate and hide any variability in the field. In the citrus grove, intra-parcel as well as inter-parcel variability is observed.

Fig.7: NDVI vegetation index of the canopy for each plant.

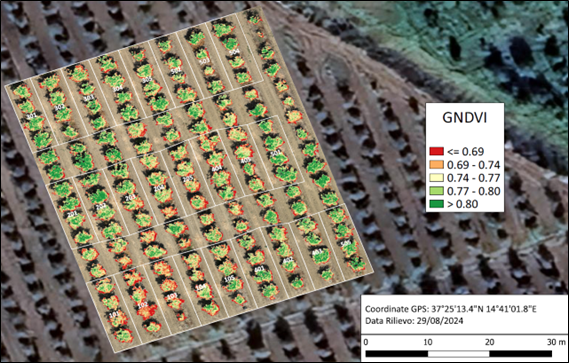

The GNDVI map makes it possible to monitor chlorophyll content in crops and better distinguish healthier areas than NDVI when canopies are well developed. In addition, GNDVI can be used to assess the water uptake of plants and thus their water stress. Again, there is strong variability between plots, while there is little intra-parcel variability.

Fig.8: GNDVI vegetation index of the canopy for each plant.

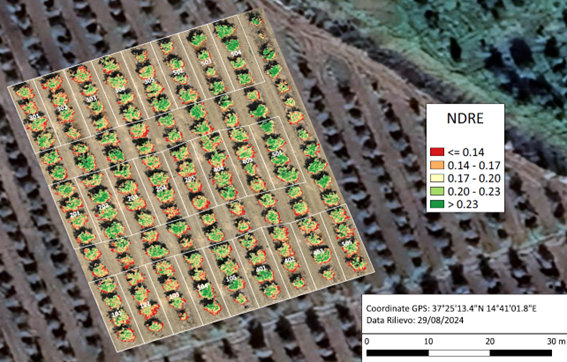

As with the GNDVI index, the NDRE map allows monitoring of chlorophyll content in crops even when canopies are well developed. NDRE is a better indicator of plant health than NDVI for medium and late crops with high chlorophyll levels. In addition, NDRE can be used to assess nitrogen uptake by plants and thus their efficiency.

Fig.9: GNDVI vegetation index of the canopy for each plant.

Conclusions

The case study conducted in the citrus grove demonstrates that artificial intelligence applied to remote sensing by drone can become a practical operational tool for agronomic decision support. The iDrone from Agrobit enables the transformation of ultra-high-resolution multispectral images into objective and measurable information on the vegetative state of crops. In addition, through the calculation of biometric parameters and vegetation indices, it was possible to identify and quantify the spatial variability of the citrus orchard, assess plant response to different treatments, and identify stress situations early. This information, which is difficult to obtain with visual monitoring alone, allows for more targeted, efficient and sustainable interventions.

In an increasingly complex agricultural environment, the iDrone service is a reliable AgTech solution to improve management efficiency, reduce costs, and support decisions based on real data.